Here’s how local operators at Hawke’s Bay Airport maintained safety in the chaotic aftermath of Cyclone Gabrielle. And what they learned about preparing for the next emergency.

Here’s how local operators at Hawke’s Bay Airport maintained safety in the chaotic aftermath of Cyclone Gabrielle. And what they learned about preparing for the next emergency.

This is the second part of the Lessons from the cyclone article. To read the first part, see Lessons from a cyclone - part 1.

On this page

Marshalling in the 'bedlam'

Photo courtesy of Skiv Devesovi/Aroha Helicopters.

“At first, it was just a trickle of aircraft coming in from outside,” says Arsel Aslam, Chief Operating Officer of the Part 135 Air Napier.

“But then the pleas, in particular for generators, from people in Hawke’s Bay to family and friends outside the region, resulted in GA aircraft flying in from all points – it was bedlam.

“There was no one person organising movements of aircraft on the ground, so we decided we may as well offer.

“It wasn’t completely foreign territory for us. We do ground handling, and we organise private jet arrivals at the aerodrome, so we thought, ‘why not?’”

Over the next 21 days, Arsel marshalled the ground movements of many hundreds of private aircraft, while his brother, Shah, oversaw their own Air Napier flights. Demand for these grew by 300 percent as power companies and surveying companies, and roading and forestry consultants, wanted to get into, and around, the district.

“The challenge was in making sure the C130 flying in, full of supplies from Ohakea, and the 172 from the Rotorua Aero Club, also packed with supplies, stayed out of each other’s way on the ground.

“We were lucky that the airport already had seven gates and we created an eighth, temporary, one in front of our hangar, to move the little guys away from the big ones.”

Establish relationships ahead of time

“I’d say the most important thing, ahead of any event, is to build relationships with other operators,” Arsel says.

“Have regular meetings about, ‘What if? How do we all fit in?' Organise who does what in what circumstances.

“You can’t plan right down to the last point. Depending on the emergency and the damage and who’s available on the ground, you’re going to have to just ride it, adapt, be innovative, and do the best you can.

“But yeah, getting together with other users of the aerodrome and going through some sort of visualisation of an emergency and who is best to do what, would be my first piece of advice.”

Historic airspace restrictions

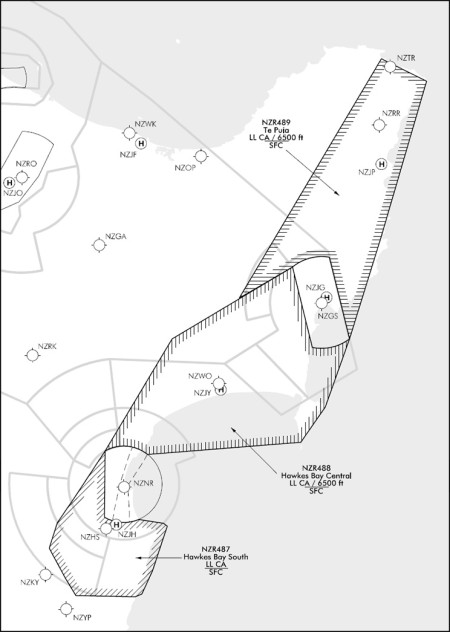

Source: Aeropath Aviation Information Management

The CAA restricted airspace in the Napier control zone on Day 3 – Thursday 16 February – in the Gisborne control zone on the morning of Day 4, and in uncontrolled airspace that afternoon.

CAA Aeronautical Services Manager, Sean Rogers, says any earlier would have been counter-productive.

“Because of the lack of comms, nobody really knew what was going on.

“All we knew was that the tower was out, and that people were being lifted off their roofs.

“We felt if we put in restricted airspace at that time, we’d limit those Section 13A activities.

“We wanted to make the best decision at the appropriate time based on the best available information.”

On Day 3, the aeronautical services team made contact with two CAA staff members who were in the Hawke’s Bay.

“They sent us real-time information about what was needed. With Airways back in action, we restricted airspace over the control zone – mainly to allow Air New Zealand flights in, carrying essential personnel and supplies.

“Then we looked at the rest of the region and what was needed there.”

What resulted was the biggest airspace restriction in New Zealand history.

The damage wrought by Gabrielle was so widespread, and the response so necessarily large, that restricted uncontrolled and controlled airspace stretched from Te Araroa in the north to Hastings in the south (see diagram). It remained in place until 27 February1.

The maintenance facility

Photo courtesy of Skiv Devesovi/Aroha Helicopters.

Red Airworx was one of the two maintenance facilities at the aerodrome without power for the first six days.

“If there’s an event headed your way,” CEO Rob Mudgway advises other workshops, “your first thoughts should be ‘where’s the power, food, water coming from?’

“We were overwhelmed with ‘cyclone refugees’ arriving at our base, all needing food, water, toilets, pickups and drop offs – and helicopters needing maintenance.

“We couldn’t, at first, carry out necessary maintenance on rescue and recovery aircraft due to the lack of power, so a generator was our first requirement.

“But our hangar didn’t have a facility to plug the generator into the mains system, so not only should you have a generator, you need to also have the facility to be able to connect it to the mains.”

Another piece Rob is happy to impart, is that if a workshop doesn’t have power, ask whoever is hooked into the daily civil defence briefings, to pass on that request.

“I didn’t think to reach out to the airport company until Day 5 for support in getting full power to our facility.

“Once Deb Suisted realised what was going on, she asked at the civil defence video briefing, and we had Unison out here within 15 minutes.

“So think about who you can ask!”

The schedule

Photo courtesy of Skiv Devesovi/Aroha Helicopters.

The first C130 arrived at Hawke’s Bay Airport on Day 3, carrying oxygen bottles for first responder operations. The second flew in on Day 5, packed with water, food, comms equipment, and nappies.

Flight Sergeant Steve Knapton was in Napier, checking on his family and house, having flown in from Auckland just behind the cyclone, on Day 2.

“I’d flown for 10 years as an Air Loadmaster on C130s and Air Napier called on Day 5, asking if I could give them a hand unloading a C130, because they had no experience with that.

“The next day, I received a call from the Headquarters Joint Forces of New Zealand, asking that I open an air bridge at Napier.

“So my job for the next few weeks was to maintain an NZDF ‘air terminal operation’. That’s basically creating a safe physical place at the aerodrome where all the equipment gets unloaded and loaded, personnel disembark and embark and aircraft are parked and despatched.

“That sounds pretty straightforward but it became complicated quite quickly.

“We had a specialist forklift flown in by C130 to safely accommodate large air freight pallets needing to be unloaded. We also needed to have a secure area for transferring those pallets safely onto trucks or other vehicles.

“We had passenger movements in and out of Napier, mostly NZDF personnel, so we needed a safe waiting area for them. And there were multiple RNZAF King Air flights carrying the prime minister and other senior people, those VIPs needing a secure meeting area.

“There were rotary-wing aircraft based over at Bridge Pa (Havelock North aerodrome) which were flying people and supplies into Napier.

“And we had all of this while making sure non-NZDF and other flight operations were not disrupted, and everyone was safe.”

Photo courtesy of Air Napier

It all came down to ‘the schedule’. Steve had to liaise with various branches of the NZDF to find out the arrival times of various military aircraft flights, and then safely mesh that with other airport traffic.

He worked closely with Arsel Aslam from Air Napier, who was marshalling the ground movements of civilian flights.

“We NOTAMed off the military area at the airport, so it was kept separate from other operations. You didn't really want to have a Hercules on the ground, with people being transferred from it, and a helicopter landing behind it in the small area we had,” says Steve.

“I wrote up a flight board so Air Napier personnel could work around the military flights and the Hawkes Bay Airport manager had some idea of our activities.

“And we did manage to keep everything separate. It was probably our biggest success. Air Napier were outstanding in their marshalling of the civilian aircraft. At no time did I ever think, “Ohhh, that could have been a bit of a mishap’.”

What would Steve recommend to other jurisdictions who may face a similar natural disaster?

“We were able to handle the amount of traffic as it was, but if there had been more flights, if I’d been handling multiple C130 arrivals, we would have required a ground liaison person with a ground-to-air radio, coordinating where all these aircraft needed to park.

“I’d envisage a formal parking plan, with someone in my role communicating with that ground liaison person each morning, saying something like, ‘Here’s what I’m expecting today’. They could then work out ahead of those arrivals about where to position them once on the ground.”

By the numbers

| Number of military flights 14 February – 7 March | 72 |

| Highest number of defence force movements in 4 hours | 10 |

| Increase in VFR day flights between January and March | 350% (305 to 1369) |

| Tonnes of cargo moved 14 February – 7 March | 500 |

| Cash delivered for the Reserve Bank in one flight to Gisborne | $41 million |

| Number of forklifts available on Day 2, to move nine tonnes of cargo – water, nappies, dried milk, ATMs – from C130 | 0... |

| …Number of family members and friends of Air Napier employees who, on Day 2, formed a human chain to move nine tonnes of cargo – water, nappies, dried milk, ATMs – from C130 | 20 |

| Number of days Air Napier’s Arsel Aslam worked straight | 25 |

| Number of hours Arsel worked each day | Up to 18 |

| Increase in the number of Air Napier flights, 14 February to 7 March, over average | 900% |

| Number of phone requests for charters made to Air Napier on Day 3 | 359 |

| Number of litres of fuel flown between Hastings Bridge Pa aerodrome and Hawke’s Bay Airport in the first three days | 500 |

The ambulance service

Photo courtesy of Skiv Devescovi/Aroha Helicopters.

The air ambulance service, Skyline Aviation, was tracking the cyclone as it made its way down the North Island, and began to prepare.

But, like everyone else, the scale of the emergency was unexpected.

“The severity of the impact on Hawke’s Bay surprised us,” says Dylan Robinson, Group and Quality Manager for the NZ Air Ambulance Service (Skyline Aviation).

“We were anticipating bad weather but not to the scale of destruction we woke up to on 14 February.

“We did have satellite phones but these proved patchy at times in Napier, so communication remained the biggest challenge throughout the week.

“Our base was equipped with a generator, but frustratingly, it gave up on Day 1.

“Although we’d tested the motor once a week, we hadn’t routinely tested it under load. So as soon as we needed it to do some heavy lifting, it died. Fortunately, we were able to source a new generator the next day.

Like every other operator, the workload was enormous.

“We completed more than 100 emergency response flights in the first weeks while still providing our normal daily ambulance service around the country, and to and from the Pacific.

“The Wairoa community relies on our fixed wing service for patients to access Hawke’s Bay Hospital.

“Normally we provide air ambulance flights to Wairoa four to five times a week,” says Dylan. “But those first weeks after Gabrielle Wairoa was completely cut off, so we were flying up there up to ten times a day.”

The flights ranged from intensive care operations, and medivac of patients needing tertiary care, to freight flights in their cargo-configurable aircraft, shipping medical supplies, water, food and other essentials to Wairoa Hospital and refuge centres.

Wairoa locals helped unload the first flight at 6am, and were still helping late into the night, unloading subsequent flights, and helping deliver aid goods to the hospital and refuge centres.

Safety in the melee

Photo courtesy of Skiv Devesovi/Aroha Helicopters.

“Hawke’s Bay Airport was a really busy place, because it was also the military, rescue, and police helicopter staging area. This meant there was a lot of extra air and ground traffic,” says Dylan.

“So, as a mitigation we made sure our aircraft were always operating with two pilots to ensure extra situational awareness.”

Fatigue was another area the flight ops team kept an eye on. Flights from Napier to Wairoa are short, usually only around 10-15 minutes long.

“Those short flights are more fatiguing than longer flights, so we made sure our team were able to be swapped out with pilots coming in from rest days.

“Starting to stagger rest days for crews as soon as possible was key to making sure we always had pilot coverage after a few busy days.

“We were also fortunate to be able to bring in some of our pilots and nursing staff from other bases around the country.

“It’s tempting to get all hands on deck in the first couple of days, because there’s so much to be done.

“But we said to a number of our guys, ‘Stay home, get rested, we’re going to need you soon’.”

Dylan advises any other operator facing a similar event to have the self-restraint not to “use all your resources straightaway”.

“It was hard for some pilots, as they wanted to get in and help, but we insisted, and it was definitely the right thing to do.”

The tower

Photo courtesy of Skiv Devescovi/Aroha Helicopters.

For the first two days, flooded roads and broken bridges prevented Airways staff getting to work.

The control zone at Hawke’s Bay reverted to see and avoid, and ADS-B appears to have done most of the heavy lifting to maintain situational awareness.

Arsel Aslam, from Air Napier, says it was interesting to see what the lack of official ‘control’ meant.

“The pilots coming in made exemplary radio calls, position reports, and used see and avoid. It was a great example of what can happen to benefit safety, if everyone plays the game according to the rules.”

Two Airways staff were able to provide an air traffic control service on Day 2 – a period of intense rescue and recovery traffic. But once their shift was over, it was back to see and avoid for the pilots because air traffic controllers are not permitted to work double shifts for safety reasons, and no replacement staff could reach the tower.

By Day 3, however, the tower was more than fully staffed – with two controllers per shift (normally, Hawke’s Bay is a ‘solo’ watchtower) to cope with the huge workload.

The nearest tower at Gisborne was also dealing with the emergency, but was staffed throughout and able to communicate with pilots, if not the outside world.

Napier Chief Controller Rainier Bron says the demands were unprecedented.

“We’d never seen anything like it. And it happened so quickly.”

Over the week, the Napier tower had 55 itinerant helicopters coming and going from the control zone – in addition to the local operators who were also part of the response.

“Normally it’s a handful for an entire day. We definitely needed two people on. The number of phone calls on top of radio calls from small itinerant aircraft in those first few days was quite intense.

Rainier Bron, Chief Controller, Napier tower

“On Day 5, survey aircraft entered the mix, as they flew survey lines predominantly over the area in the control zone, which increased the complexity of our work.

“And adding to that was managing the four NZDF NH90 helicopters and the two Australian Spartan aircraft, with all the other rescue and recovery traffic.

“It was certainly unrivalled in my experience. It was challenging and stressful, but it was also rewarding to be able to support pilots to do their job.”

Asked by Vector about preparing for another event, Rainier says the only way to plan for the unpredictable is to ensure that training and procedures are robust and comprehensive.

“It does show why continuing to invest in good training is so important,” he says. “Because that’s the thing that probably saved everyone’s bacon.

“Our good training allowed us to cope with the level of traffic that eventuated.

“And the pilots’ training was also obvious to us – in general, their professionalism was awesome.

“Investing in technology is also important. ADS-B gave us a much safer way of controlling such a busy airspace, with all those aircraft operating and doing random manoeuvres.

“It was clear to us the difference ADS-B made in those first few days, and that was great because it did feel like we were the busiest airport in New Zealand for a couple of weeks.”

Safety, despite the mayhem

Photo courtesy of Skiv Devescovi/Aroha Helicopters.

“Why would we want an incident?” responds Arsel Aslam, from Air Napier, when asked if even a little bit of safety was sacrificed to the overwhelming need for goods to be flown into, and around, the region, and to have them quickly distributed.

“Why on earth would I risk a plane propellor versus human during such a stressful time? Of course we maintained safety standards,” he says.

“We had to learn about safety around C130s while their engines were still running,” he says. “Where to walk to get into the aircraft, where we park stuff, where and how we move stuff, stopping people, waving them to ‘their’ gate.

“We also made sure there was no double handling of cargo, no wheeling out there of trolleys, putting the stuff on trolleys, bringing them back – the more we handled the cargo, the higher the risk something could go wrong.

“So we just brought the cars in, one at a time, filled them or the trucks up with all the goods, moved them back out nice and simple, nice and easy. If there were multiple planes, they just had to wait their turn.”

Working with Arsel was Steve Knapton, the NZDF Air Loadmaster, who was responsible for safety around the C130s and other military aircraft.

“We knew when civilian aircraft were coming in, and we had people at the wing tips of the parked aircraft as safety guides, even though some of those smaller aircraft could technically taxi underneath the wing of a C130.

“When we had passengers coming off the aircraft, we used Air Napier people as aim points for disembarking passengers to safely walk across the apron to the Air Napier terminal.”

Apron safety

“We had a lot of people arriving at our base,” says Red Airworx CEO Rob Mudgway. “And yeah, we did work hard to make sure everyone was safe.

“So our gate to airside was kept closed, and we informed people needing to fly out or collect freight and so on, that they had to wait on our side of the gate for their pilot to collect them.

“Most people were great and understood the dangers. Others just needed a gentle reminder.”

Checklists and problem solvers

In a recent presentation to the NZ Airports Association about what she’d learned from Cyclone Gabrielle and its aftermath, Deb Suisted said that, while her team knew what to do instinctively, “If we couldn’t get to the airport we would need a checklist of ideas and tasks so anyone could get the airport up and running. You can’t plan for every emergency, but a checklist of what to think about might help someone without our experience.”

She also told the conference, “It’s the problem solvers who help you. Know who they are so you don’t waste time trying to solve a problem with those who can’t, or won’t, think outside the box.”

Footnotes

1 Fire and Emergency NZ is conducting an operational review of its work in administering uncontrolled airspace restrictions and didn’t want to comment publicly until that review is complete.